Schools are dynamic environments surrounded by static brick and mortar. Schools are a complex entanglement of systems clinging to normalcy led and composed of individuals seeking growth and progress. There is constant turnover as students move through the systems, gaining mastery, seeking support, and receiving guidance. Employees similarly move often as they change roles and responsibilities, as cultures emerge and evolve, and as individuals retire, are hired, or move on to other positions, commonly referred to as “job rotation.” This constant change affects a school’s culture and climate as each is achieved through sustained efforts. When change is present within the school leadership, specifically those identified as assistant principals within their organizational hierarchy, the impact on school culture may be even more dramatic than the effects felt with the turnover of students and teachers.

This study examines the job longevity of current assistant principals (APs) while exploring the existing research examining the need for decreasing mobility of those who occupy this role for the betterment of school culture and long-term success.

Statement of the Problem

There is both an explicit and implicit hierarchy within schools. Building administrators, principals, APs, and deans are typically viewed as the leader. Their style and direction drive the school. The priorities that they establish are taken as the priorities for the school (Lee et al., 1993). Their personality filters through the staff and students. Traditionally, however, individuals in these roles do not possess substantial job longevity and, therefore, experiential expertise.

An increase in job longevity can lead to an increase in time-on-tasks associated with the role and an increase in expertise (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). APs, the administrators who tend to have the most direct student contact, are extremely prone to seeking new employment after only a short time of refining their skills and, as a result, may not achieve expert status (Marshall, 1993). When APs leave to assume a new role, they may be enhancing their own perceived power and prestige but there is a cost associated, especially in the school left behind. Identifying who the individuals are who possess the role of AP, their demographic and motivational characteristics may allow schools to enhance strategic hiring and training practices, to increase longevity, decrease mobility, and allow for greater capacity for APs as they begin to embrace their role and not simply see it as a means to another promotion and the acceptance of new responsibilities that they may not be prepared for (Bush, 2019).

Coupled with a literature review and a demographic analysis, the purpose of this study is to examine how current demographic characteristics compared with those utilized in past studies. Specifically, do APs today continue to possess characteristics of high job mobility and relatively short-term job tenure?

AP Role Definition

For some, the role of AP is viewed as a stepping stone, a hoop to jump through the way to positions that offer perceived higher levels of power and prestige. It is a training ground where leadership and managerial skills can be enhanced. For others, this role is viewed as a career that carries with it a long tenure and sustainability. APs begin their roles by distancing themselves from those in lower-level positions and adapting to what is expected by other administrators. This behavior continues throughout their career, a constant game of adaptation and conformity. The motivating factors behind such behaviors are complex and plentiful.

Much effort is put into working on tasks that might make an individual marketable, yet the single most important component appears to be earning the support of others in the profession. “People in almost any culture are reluctant to offend superiors” (Bolman & Deal, 1997, p. 23). In fact, those who are hopeful of earning a promotion are cautious not to stand out but to act in a way that conforms to those already at higher levels. Strang and Soule (1998), who wrote about the need for connectedness within organizations, stated, “Strong ties lead actors to take the perspective of the other and to exert powerful pressures for conformity” (p. 272). This is in harmony with what is needed to enter the profession.

There is no single explanation to describe the behaviors of all, but there is an abundance of literature that explores the topic. Marshall and Hooley (2006) wrote, “It is important to examine whether the salary and status of assistant principals are sufficient for maintaining the integrity of the position” (p. 130). Beyond this, they reported, “Many people chafe under the restrictions of being an assistant in hierarchical organizations . . .” (p. 127).

Marshall (1993) listed many of the workplace incentives that encouraged APs to remain in their roles.

• Collaborative site team leadership

• Being valued by the principal

• Having the flexibility and time to develop pet projects for the school

• Consistency in policies from above

• Noninterference in their jobs

• Policies supporting professional associations • Salary, benefits, and awards

• Being recognized as special.

Not all APs, however, decide to make that position their lifelong career; in fact; very few do (Marshall & Hooley, 2006). APs are, after all, individuals first, and, as such, have distinct personalities and motivations. These distinctions, in turn, carry distinct goals and ambitions. As Morgan (2018) identified, APs carry with their motivations and drivers of success, that when nurtured can lead to positive school cultures and climates and increased levels of student success. APs do not live and work in a world of isolation, however. There are a number of variables that are simultaneously pushing and pulling them toward their respective career futures. APs are a part of a larger culture. Each serves a building and, as a result, also serves a district and community.

Districts carry characteristics that are either appealing or disconcerting to APs. A district may serve a community that is rural, suburban, urban, or some combination. Because each school district serves a specified community, the norms and values of surrounding areas often permeate into the district. This simple demographic distinction may play a

part in helping a current AP decide whether his or her current role is sustainable.

Motivational Impacts

The level of empowerment afforded to an AP is another school descriptor that affects job sustainability or mobility. For some individuals, feeling empowered is not related to their motivation type; for others, it may be critical. APs enter into their roles for a variety of reasons. Once employed, they carry a level of authority simply because of the position they fill, yet APs, personally, do not always feel as though they possess the same level of authority and power that others may perceive the position to have. This perceived level of workplace empowerment can affect the job-seeking behaviors displayed by APs.

Formed in childhood and either perpetuated or dismissed as the individuals continue through a career, biases and opinions related to age, race, and gender may play a part in whether persons feel that they are marketable (Marshall, 2006). If persons feel that there are factors that may inhibit their ability to gain access to higher levels of employment, they may not search as actively as those who do not perceive the same obstacles. As a result, some may demonstrate a career history filled with past sustainability, whereas others may display evidence of continuous mobility. Each of these factors may affect whether an individual’s motivational needs are being met.

Robert Frost (1916, p. 3) wrote “Two roads diverged in a yellow wood.” Motivation also involves a diversion. Intrinsic motivation leads to one career outcome and outlook, extrinsic motivation to another (Kohn, 1986). A more complete understanding of this phenomenon will enable districts and individual schools to better meet the needs of APs, to gain a better insight on the AP’s role and influence upon students and staff, and, more importantly, to help school leaders make better decisions when hiring APs.

Individuals often select a position simply because they were given an opportunity (Scott, 2008), and districts often offer an opportunity simply because an individual possesses leadership potential. It may be ironic when individuals are selected for a position because they actively pursued a new opportunity and are then expected to remain with an organization indefinitely or abandon thoughts of moving to another position. Likewise, it is ironic when individuals are selected for one position and, while undertaking the role, are simultaneously being groomed for another school leadership role. This conflict often results in limited longevity. Some districts expect loyalty and maintenance, whereas others expect initiative and aspiration. The same dynamics exist among individuals and conflict develops when there is not a fit. Districts should select APs who have the same motivations and aspirations as the district (Marshall & Hooley, 2006). A match will enable greater harmony, trust, and job satisfaction. If expertise is generated from experience and time on task, districts may want all staff members to gain as much expertise as possible.

Thompson and Hawkes (1962) stated, “In American public education . . . the tendency has been to insist that competence related to the organization’s technical core be an essential ingredient for the administrator” (p. 15). Typically, at the elementary level (k–5), this task is done by one building-level administrator, a principal. At the secondary level (6–12), it is becoming rare to find one individual who is solely responsible for the administration of all school functions. Commonly, the principal at the secondary level is accompanied by one or more APs to help manage and lead the school. Typically, at all levels, an administrator will be expected to possess knowledge of the core work of educating children, but the work of an AP is often more complex. The position grew out of a need for expediency rather than to serve a specific purpose (Mertz, 1999). To highlight this point, Gorton et al. (1988) failed to even mention the AP role in The Encyclopedia of School Administration and Supervision (Marshall & Hooley, 2006).[AQ: 6]

The Recent History of the Role

Although the role of the AP was not designed with a real purpose in mind, it is often described as a “do-as-you-are told” position (Austin & Brown, 1970). A more recent study described the duties of APs in more detail, as shown in Table 1 (Armstrong, 2004).

Table 1. Duties of Secondary Assistant Principals in Texas Reported in Order of Frequency.

Discipline

Campus/building safety

Student activities

Building maintenance

Teacher evaluations

Attend ARD, 504 meetings

Textbooks

Duty schedule

Tutorial programs/at-risk programs

New teacher/mentor programs

Assessment data/TAKS

Staff development

Community activities

Attendance

PEIMS

Graduation

Campus decision-making team

Lockers

Master schedule

Curriculum development

Transportation

Keys

Parking

(p. 66)

At least at the secondary level in the State of Texas, it appears that APs see their role as more of a manager than a leader. “Assistants are seldom expected to assert leadership by creating new projects or initiatives. Risk-taking must be limited; assistants must confine themselves to supportive tasks, leaving visible leadership to the principal [hierarchical upper-level]” (Marshall & Hooley, 2006, p. 7). APs are not expected to enhance their own individual agendas but to “make decisions . . . as the organization would like him to decide” (March & Simon, 1958, p. 62). Scott (2008) wrote, “Institutions constrain and regularize behavior . . . regulatory processes involve the capacity to establish rules, inspect others‟ conformity to them, and, as necessary, manipulate sanctions” (p. 52).

APs often become administrators after spending time as a classroom teacher. Upon receiving their initial appointment, they “have already gone through anticipatory socialization, a period in which they think about administration; watch administrators’ activities, behaviors, and attitudes; and start to transform themselves into administrators” (Marshall & Hooley, 2006, p. 35). It is fascinating that despite a study by Winter and Partenheimer (2002) that identified that “the general pool of teachers view[s] the job of assistant principal as unattractive” (p. 12), there are countless numbers of educators who seek this role. Those who actively seek the role may do so with unrealistic expectations, believing that they will be more involved with instructional supervision. Gross (1987) found that when administrators entered their role with this predisposition, it helped them transition into their initial administrative role from the classroom, but it did not help them when attempting to move into higher positions.

As Hartzell et al. (1995) reported, APs rarely enter their position with the knowledge of what their job entails. Yet as Merton (1964) explained, when teachers begin to think about a career shift toward administration, they begin experimenting with tasks they believe to be administrative in nature.

Marshall and Hooley (2006) argued that achieving sustainability is crucial toward maintaining the integrity of the AP role, that constant turnover and mobility among APs do not allow individuals to gain expertise in this role. The high rate of turnover and mobility also helps to make the case against the importance of the role, as the appearance is that somebody new is capable of succeeding in the position every couple of years.

Organizations (School Descriptors)

The design and structure of organizations has been a widely studied phenomenon (Scott & Meyer, 1983; Thompson, 1962). All organizations must establish their “domain” (Levine & White, 1961, p. 585). The organization must determine the range of services rendered, the population served, and the range of products produced. Organizations are highly complex yet are part of the wider social system and are shaped by the society in which they reside (Parsons, 1960). Because of this, it is difficult to study any organization in isolation; it is essential to study it in the context of society as a whole. Thompson and Hawkes (1962) stated, “The public school, for example, which is constrained to accept virtually all students of a specified age, under conditions of population growth has an urgent need for power with respect to those in the task environment . . .” (p. 36). Public schools have very little control over their clientele, as they serve any child who resides within its attendance area. The control that schools are able to exert, however, comes from how these products (the children) will be served and how their futures will be shaped.

Thompson (2008) stated, “The technology of education rests on abstract systems of belief about relationships among teachers, teaching materials, and pupils . . .” (p. 19).

Districts have little control over which students they serve but have complete control over who is hired as staff. Staff members are individuals with the ability to act independently but are often shaped by norms present in the organization (Parsons, 1960). Districts hire individuals not to be renegades and change what is done, but to enhance and perpetuate what is already being done. The routines and practices that are in place become a “system of rules” that are expected to be followed by those within the organization whether newly employed or a veteran (Hanks, 1991, p. 3).

Schools are highly rational and are the workplace for a variety of professionals. Scott and Meyer (1983) defined rationalization as “the creation of cultural schemes defining means-ends relationships and standardizing systems of control over activities and actors” (p. 74). DiMaggio and Powell (1991) said professionalization is “the collective struggle of members of an occupation to define the conditions and methods of their work” (p. 70). Schools are very different than they were even 20 years ago, yet much is still the same. There is much routine and repetition in the way things are done. Lave and Wenger (1991) described this as “legitimate peripheral participation,” where newcomers to an organization begin to take on characteristics of the organization, “By this we mean to draw attention to the point that learners inevitably participate in communities of practitioners, and the mastery of knowledge and skill requires newcomers to move toward full participation in the sociocultural practices of a community” (p. 29). Staff members begin to conform to the expectations of their employer.

Thompson (1962), writing about organizations as a whole, stated, “The central function of administration is to keep the organization at the nexus of several necessary streams of action …” (p. 148). This is done in a number of different ways. There is no agreed upon method for successfully manipulating the actors into one common focus.

Administrating involves more than simply holding a position and occupying an office. Often, it is a team effort created by the establishment of a hierarchy of power. This is a process whereby each level on the hierarchy establishes the role definition for the level beneath it (Simon, 1957).

At the upper levels of the hierarchy, the primary goals are to diminish the amount of role uncertainty and to resolve the conflicts for the lower levels (Boulding, 1964). The task designed for all administrators is to attempt to gain clarity on foggy issues and to mesh multiple personalities and agendas into one common purpose. It is rare that this function is done by one individual; instead, power is often decentralized. This, in turn, leads to more opportunities for “power positions” to be established (Thompson, 2008, p. 129). The AP is one such position that is created to fill a low-level role in the district administrative hierarchy.

Personal Descriptors and Their Impact on Administrative Selection

Marshall (1989) made a persuasive argument indicating that women and minorities have been overlooked too often in filling school administrative positions. She argued that women, especially, have demonstrated competencies that would enable them to serve as successful leaders of schools, particularly in schools that follow the national trend of being staffed by a majority of females.

Because it is extremely difficult to acquire reliable information on APs, the following statistics on public school principals are offered by Marshall and Hooley (2006). There was a remarkable increase in the number of principals younger than age 40 during the 1990s.

As a low-level administrator, it is reasonable to assume that the number of APs, nationwide, younger than age 40 has risen as well. Because of the relatively young age of many of the new administrators, it is likely that individuals who are currently being hired to fill the leadership roles possess needs that vary substantially from those of previous generations. A recent study of the private sector found that younger employees tend to place importance on relationships with co-workers and supervisors, desire professional growth experiences, and enjoy challenging assignments (NAS Recruitment Communications, 2007). Thus, a value on intrinsic motivation seems to be prevalent among young workers in the private sector. Whether this is true in the public sector, specifically within the educational leadership community, is yet to be seen, but recent research examining young teachers, the starting point for most school leaders, shows similarities (Behrstock & Clifford, 2009). As a result, many young educators find themselves extremely mobile in search of a position that meets their motivational needs.

A study by the Alliance for Excellent Education (2008) reported that each year 157,000 young teachers leave the profession and another 232,000 move to new positions within education. Although these figures represent teachers, it has been previously reported that teaching is the primary career starting point for most APs and therefore, a large number of APs begin their careers in education as highly mobile employees.

Motivation Theory (Extrinsic and Intrinsic)

All people are motivated by something. The complexity of possibilities can be simplified by reducing personal motivations into extrinsic and intrinsic motivators. Deci and Ryan (1985, 2000) are leading researchers of motivational factors and their impact on social settings. Together, the authors have developed a self-determination theory, which attempts to explain how social and cultural factors facilitate or undermine people’s sense of volition and initiative in addition to their well-being and the quality of their performance. Johnson and Johnson (1985) described extrinsic motivation as the driving force behind completion. Extrinsically motivated people are intent on receiving something that is outside of them: a tangible reward, a feeling of power, a declaration of being the winner, or simply praise and adoration. Conversely, intrinsic motivation concerns needs and wants within an individual. Clifford (1972), a clear proponent for this motivational style, wrote, “Performance is dependent upon learning, which, in turn, is primarily dependent upon intrinsic motivation” (p. 134).

Deci (1972) pioneered research in this area of humanistic psychology. In the early 1970s, he conducted a series of studies that demonstrated the distinctions between extrinsic and intrinsic motivations. Extrinsic motivations involve a system of rewards and punishments for specified behaviors. Intrinsic motivation in people involves an “inherent tendency to seek out novelty and challenges, to extend and exercise their capacities, to explore, and to learn” (p. 119). Herzberg (1966) was one of the earliest researchers who argued for the importance of studying intrinsic motivation, stating that what is rewarding gets done, not that which is rewarded.

In their study, Kasser and Ryan (1996) developed seven distinct categories of motivation. Intrinsic motivators include personal growth, relationships, community, and health. Health was later removed from their list as subsequent studies demonstrated a low correlation to any identifiable social phenomenon, and health could not be easily identified as either intrinsic or extrinsic. Extrinsic motivators include wealth, fame, and image.

In spite of the work done by Herzberg (1966), Clifford (1972), Deci (1972), Ryan (1982), and others, extrinsic motivation is still seen by many in American society as the only true form of motivation, especially at the workplace. Daily, in virtually every organization, employees are given tangible gifts and rewards for their services (Bolman & Deal, 1997), the thought being the greater the reward, the harder people will work.

Those who create the structure have designed what they believe is an incentive-driven climate where those who work the hardest will get the most rewards. Yet as Deci (1972) wrote, “When money is used as an external reward for some activity, the subjects lose intrinsic interest for the activity” (p. 120).

For those who are currently employed as APs, a number of factors may drive the search for mobility for those so inclined, beyond a quest for money.

Perhaps the tangible rewards some are given in their current employment setting are actually pushing them away. In another study from the 1970s, it was reported that some extrinsic motivators actually decrease productivity and job satisfaction (Lepper et al., 1973). As people begin to work toward obtaining goals established by others, to receive rewards from others, they lose their autonomy.

AP–Mobility and Stability

Once chosen, APs tend to spend their early years learning the procedures of their school and their later years maneuvering to receive a higher-level position. Little time is spent acquiring expertise in the task functions associated with the AP’s role (Marshall & Hooley, 2006).

Gaertner (1980) discovered that the assistant principalship is a good stepping stone role for school leaders. In 1994, more than half (54 %) of principals surveyed had previously held the position of AP (Fiore, 1997). Specifically, Marshall (1985) studied the roles of 20 APs to discover what tasks were performed to make them more attractive for higher-level positions in the future. Seven such tasks were identified:

• Initially deciding to leave teaching,

• Analyzing the selection process for initial entry into the profession and upward mobility,

• Maintaining calm in crisis,

• Defining professional relationships,

• Becoming a street-level bureaucrat,

• Identifying and defending one’s work territory, and • Discipline management (p. 39).

The more successful an AP was in each of these task functions, the more socialized he or she became to being an administrator, and was marked for either a long-term assistant principalship or future promotion.

For those who decide to seek promotion or upward mobility, sponsorship appears to be the most critical component to successfully earning a new career (Ortiz, 1982).

Much effort is put into working on tasks that might make an individual marketable, yet the single most important component appears to be earning the support of others in the profession. “People in almost any culture are reluctant to offend superiors” (Bolman & Deal, 1997, p. 23). In fact, those who are hopeful of earning a promotion are cautious not to stand out but to act in a way that conforms to those already at higher levels. Strang and Soule (1998), who wrote about the need for connectedness within organizations, stated, “Strong ties lead actors to take the perspective of the other and to exert powerful pressures for conformity” (p. 272). This is in harmony with what is needed to enter the profession.

APs begin their roles by distancing themselves from those in lower-level positions and adapting to what is expected by other administrators. This behavior continues throughout their career, a constant game of adaptation and conformity. The motivating factors behind such behaviors are complex and plentiful. There is no single explanation to describe the behaviors of all, but there is an abundance of literature that explores the topic. Marshall and Hooley (2006) wrote, “It is important to examine whether the salary and status of assistant principals are sufficient for maintaining the integrity of the position” (p. 130). Beyond this, they reported, “Many people chafe under the restrictions of being an assistant in hierarchical organizations . . .” (p. 127).

Marshall (1993) listed many of the workplace incentives that encouraged APs to remain in their roles. Not all APs, however, decide to make that position their lifelong career; in fact; very few do (Marshall & Hooley, 2006). “APs are after:

• Collaborative site team leadership,

• Being valued by the principal,

• Having the flexibility and time to develop pet projects for the school,

• Consistency in policies from above,

• Noninterference in their jobs,

• Policies supporting professional associations, • Salary, benefit, and awards”

All, individuals first, and, as such, have distinct personalities and motivations. These distinctions, in turn, carry distinct goals and ambitions.

Career Future

Over time, organizational actors are assimilated into the culture of the organizations. As time and experiences progress, actors begin to acquire organizational expertise. It is imperative to determine how districts and schools can better motivate those people in leadership roles to endure to gain knowledge and expertise to better affect the school and community. Perhaps with this knowledge, districts will be better equipped to make hiring decisions that meet their community norms. By having a basis for determining when or if the newly hired is prone to begin searching for a new position, the district can be better equipped to give the individual the training and tools needed to successfully seek or it can give him or her the motivation necessary to remain as an employee. Because it is extremely difficult to acquire reliable information on APs, the following statistics on public school principals are offered by Marshall and Hooley (2006).

In 2000, there were 83,790 public school principals. 56% of public school principals were male (47,130). Eighty-two percent of public school principals were white, non-Hispanic. The next closest subgroup was black, non Hispanic at 11%. This representation, however, may not have been equally dispersed based upon community demographics as a whole.

Sergiovanni (1967) developed the motivation hygiene theory. He suggested that when people are placed in environments where there are intrinsic motivators present, there is a greater sense of work commitment and persistence. Although this theory was developed by examining the workplace of teachers and not school leaders, it moved the discussion of motivation to a new level. The motivation hygiene theory attempts to account for the motivations that are supplied by the workplace, not just the motivational needs of individuals.

Csikszentmihalyi (1990) looked at individual motivation, which was supplied by the workplace, and the interaction between the two. His theory, which he called flow theory, was developed from more than 20 years of studying motivation and its impact on social behaviors. Csikszentmihalyi suggested that when individuals are able to achieve “the state in which [they] are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter,” they have achieved flow (p. 4). When an individual reaches this state, performance is at its peak and expertise can be obtained. He believes flow is derived from a combining of forces from both the individual and the environment. Only when a person is able to experience true ownership or empowerment, coupled with a sense of personal fulfillment (intrinsic motivation), can flow ever truly be obtained.

Flow theory comes from the belief that when an individual is given the opportunity to experience flow, there is no need for extrinsic rewards or to seek greater challenges through mobility. When flow is obtained, nothing else matters except what is being accomplished at the moment. An increase in flow brings an increase in stability. A decrease in flow, or a lack thereof, brings about an increase in mobility or a quest for greater satisfaction through either new challenges or extrinsic aspirations.

Methodology and Data Collection

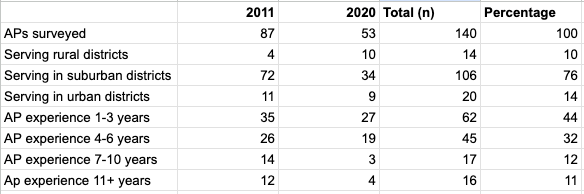

Using two recent surveys of practicing APs (Schmittou, 2011), the first in 2011 and the second in 2020, we are able to see samples that may not be representative of APs as a population, but, exploring select demographic data of the sample, allows inferences to be made and raises the possibilities for future studies.

Table 2.

Note. AP = assistant principals.

This study is quantitative in nature, using elements of both descriptive and inferential statistics. “The purpose of descriptive statistics is to organize and to summarize data so that the data are more readily comprehended” (Minium et al., 1999, p. 2). Because the goal of inferential research is to attempt to draw conclusions about the population as a whole, a large sample is required (Minium et al., 1999). This study utilizes a convenient sample, however, making it difficult to generalize to the population at large. Although the data available for the participants demonstrate similarities between the sample and the population at large, the lim

its placed upon the participants make it difficult to draw inferences beyond the limited scope of this study. This study utilizes two surveys, the first conducted in 2011 and the second in 2020. About 140 total surveys were completed by individuals who self-identified as “AP”(s). Both surveys utilized the same descriptive questionnaire, but each targeted different participants to attempt to gain greater reliability of results. In 2011, surveys were sent to all practicing APs in three counties of south-east Michigan, identified by local school district websites. Those participants identified and surveyed in 2020 were self-selected, representing 16 states, and identified via current educational leadership programs. The overwhelming majority (76%) of respondents identified their employment in a suburban community; however, participants from urban and rural districts were also represented in the results of these surveys.

Participants were asked to complete one survey, which included three sections. Only the results from Section One are reported in this study. Findings from Sections 2 and 3 will be shared along with further studies at a later date. The first section is Personal Descriptors, which consists of eight questions that collect information regarding the age, gender, work history, and attempted mobility or stability of each respondent. These descriptive statistics provide greater clarity about the make-up of the sample and four factors for measuring the career stability or mobility of participants.

Participants were asked to describe the length of employment in their current role as AP, to describe their current job-seeking behaviors, and to detail the number of buildings and districts where they have been employed throughout their career. These four variables were analyzed as the dependent variables throughout the study in relation to the various measures of personal motivation and perceived workplace empowerment levels, which are reported in subsequent studies.

Analysis and Implications of Findings

APs play a critical role in secondary public schools. The longer individuals are able to remain in their current roles, the greater the level of expertise they are able to obtain (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). The APs who participated in this study, however, possessed an average of between 4 and 6 years of experience in their current role. Of the APs who participated in this study, 92% have worked in more than one building as an educator and 74.7% have been employed in more than one school district.

The mobility of APs has a negative impact on their ability to gain expertise in their role (Marshall, 1993). The lack of AP expertise impacts the leadership and direction provided for the building at large, as each is a part of the building administration, and the priorities that the administration establishes are taken as the priorities for the school (Lee et al., 1993).

The role of school APs needs greater clarity and definition as the responsibilities associated with the role vary by building, location, and individual (Mertz, 1999). Marshall and Hooley (2006) stated, “Assistants are seldom expected to assert leadership by creating new projects or initiatives. Risk-taking must be limited; assistants must confine themselves to supportive tasks, leaving visible leadership to the principal [hierarchical upper level]” (p. 7). Lacking the opportunity to demonstrate true leadership, and having to focus on supportive tasks may contribute to attempted career mobility, as APs feel that they are capable of more.

There does appear to be a mismatch in needs between districts and buildings and the APs that they employ (Marshall & Hooley, 2006). As Hartzell et al. (1995) reported, APs rarely enter their positions with the knowledge of what their job entails. Yet as Merton (1964) explained, when teachers begin to think about a career shift toward administration they begin experimenting with tasks they believe to be administrative in nature.

Marshall and Hooley (2006) argued that achieving sustainability is crucial toward maintaining the integrity of the AP role. They said that constant turnover and mobility among APs do not allow individuals to gain expertise in this role. The high rate of turnover and mobility also help make the case against the importance of the role, as the appearance is that somebody new is capable of succeeding in the position every couple of years. This study confirms these earlier findings as APs included in this sample are highly mobile, have relatively short tenures, and as such have limited access to gaining expertise.

Future Studies

The researcher acknowledges a need to examine the motivational tendencies of current and aspiring APs to identify supportive structures to be introduced into the workforce of APs. Furthermore, an examination of those individuals responsible for hiring, training, and development of APs, examined in conjunction with identified AP needs, desires, and motivations, could yield guidance on how to improve existing practices to increase job longevity and training. In order to retain the APs currently employed, districts must make an effort to meet the AP’s needs for personal growth, relationships, and community-building. Districts should also place an increased emphasis on hiring APs who possess motivational needs that match those provided by the district and allow for a more realistic job preview to attract more AP candidates who are interested in the role of AP, not in simply using the position as a catalyst for another job.

References

Alliance for Excellent Education. (2008). What keeps good teach ers in the classroom? Understanding and reducing teacher turnover [Issue Brief]. https://all4ed.org/wp-content/uploads/ TeachTurn.pdf

Argyris, C. (2009). Integrating the individual and the organiza tion. Transaction Publishers.[AQ: 11]

Armstrong, L. (2004). The secondary assistant principal in the state of Texas: Duties and job satisfaction. University of Houston. http://wwwlib.umi.com/dissertations/fullcit/3122339 [AQ: 12]

Austin, D., & Brown, H. (1970). Report of the assistant princi palship of the study of the secondary school principalship. National Association of Secondary School Principals.

Baard, P. P., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). Intrinsic need satisfaction as a motivational basis of performance and well-being at work [Unpublished manuscript]. Fordham University.[AQ: 13]

Behrstock, E., & Clifford, M. (2009). Leading Gen Y teach ers: Emerging strategies for school leaders. National Comprehensive Center for Teacher Quality. http://www.tqsource. org/publications/February2009Brief.pdf[AQ: 14]

Bolman, L., & Deal, T. (1997). Reframing organizations. Jossey Bass.

Boulding, K. (1964). A pure theory of conflict applied to organiza tions. In The frontiers of management psychology. Harper and Row Publishers.[AQ: 15]

Bush, T. (2019). Distinguishing between educational leadership and management: Compatible or incompatible constructs? Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 47(4), 501–503.

Charles, C. M. (1995). Introduction to educational research (2nd ed.). Longman.[AQ: 16]

Clifford, M. (1972). Effect of competition as motivational tech nique in the classroom. American Educational Research Journal, 9, 123–137.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sci ences. Erlbaum.[AQ: 17]

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper Collins.

Schmittou 9

Deci, E. L. (1972). Intrinsic motivation, extrinsic reinforcement, and inequity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 22, 119–120.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self determination in human behavior. Plenum.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behav ior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227–268.

Dill, W. (1958). Environment as an influence on managerial autonomy. Administrative Science Quarterly, 2, 409–443. DiMaggio, P., & Powell, W. (1991). The new institutionalism in

organizational analysis. University of Chicago Press. Educational Research Service. (2004). Salaries and wages paid professional and support Personnel in public schools, 2003– 2004.[AQ: 18]

Fiore, T. (1997). Public and private school principals in the United States: A statistical profile, 1987–88 to 1993–94. Office of Educational Research and Improvement, Educational Resources Information Center, National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education.

Frost, R. (1916). The road not taken. In Mountain interval. Henry Holt.[AQ: 19]

Gaertner, K. (1980). The structure of organizational careers. Sociology of Education, 53, 7–20.

Gorton, R., Schneider, G., & Fischer, J. (1988). The Encyclopedia of school administration and supervision. ORYX Press. Gross, R. (1987). The vice principal and the instructional lead ership role in the public senior high school. University of Chicago.

Gulick, L., & Urwick, L. (1937). Papers on the science of admin istration. Institute of Public Administration.[AQ: 20] Hanks, W. (1991). Foreword. In J. Lave & E. Wenger (Eds.), Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.[AQ: 21]

Hartzell, G., Williams, R., & Nelson, K. (1995). New voices in the field: The work lives of first year assistant principals. Corwin. Herzberg, F. (1966). Work and the nature of man. World. Hughes, M. (1988). Developing leadership potential for minority women. In M. Sagaria (Ed.), Empowering women: Leadership development on campus (pp. 63–74). Jossey-Bass.[AQ: 22] Jepperson, R. (1991). Institutions, institutional effects, and insti tutionalization. In The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. University of Chicago Press.[AQ: 23][AQ: 24] Johnson, D., & Johnson, R. (1985). Motivational processes in cooperative, competitive, and individualistic learning situa tions. In C. Ames & R. Ames (Eds.), Research on motivation in education (Vol. 2, pp. 249–286). Academic Press. Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1996). Further examining the American dream: Differential correlates of intrinsic and extrinsic goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 280–287. Kershner, B., & McQuillan, P. (2016). Complex adaptive schools: Educational leadership and school change. Boston College Press.[AQ: 25]

Kohn, A. (1986). No contest: The case against competition. Houghton Mifflin.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press. Lee, V., Smith, J., & Cioci, M. (1993). Teachers and princi pals: Gender-related perceptions of leadership and power

in secondary schools. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 15(2), 153–180.

Lepper, M., Greene, D., & Nisbett, R. (1973). Undermining chil dren’s intrinsic interest with extrinsic rewards: A test of the “overjustification” hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 28(1), 129–137.

Levine, R., Brietkopf, C., Sierles, F., & Camp, G. (2003). Complications associated with surveying medical stu dent depression: The importance of anonymity. Academic Psychiatry, 27, 12–18.[AQ: 26]

Levine, S., & White, P. (1961). Exchange as a conceptual frame work for the study of interorganizational relationships. Administrative Science Quarterly, 5, 583–601.

Lovelady-Dawson, F. (1980). Women and minorities in the princi palship: Career opportunities and problems. NASSP Bulletin, 64, 18–28.[AQ: 27]

Lunenburg, F. C. (2012). Educational administration: Concepts and practices. Wadsworth.[AQ: 28]

March, J., & Simon, H. (1958). Organizations. The Macmillan. Marshall, C. (1985). Professional shock: The enculturation of the assistant principal. Education and Urban Society, 18(1), 28–58.

Marshall, C. (1989). More than black face and skirts: New leader ship to confront the major dilemmas in education. Agenda, 14(4), 4–11.

Marshall, C. (1993). The unsung role of the career assistant prin cipal. National Association of Secondary School Principals. Marshall, C., & Hooley, R. (2006). The assistant principal. Corwin Press.

McCarty, M., & Zent, A. (1982). School administrators: A profile. Educational Digest, 47, 28–31.[AQ: 29]

McMillan, J. (1996). Educational research: Fundamentals for the consumer. Harper Collins.[AQ: 30]

Merton, R. (1964). Social theory and social structure. The Free Press.

Mertz, N., & McNeely, S. (1999). Through the looking glass: An upfront and personal look at the world of the assistant prin cipal. American Education Research Association.[AQ: 31]

Meyer, J., Scott, R., & Strang, D. (1987). Centralization, fragmen tation, and school District complexity. Administrative Science Quarterly, 32, 186–201.[AQ: 32]

Minium, E., Clarke, R., & Coladarci, T. (1999). Elements of statis tical reasoning (2nd ed.). John Wiley.

Morgan, T. (2018). Assistant principals’ perceptions of the prin cipalship. International Journal of Education Policy and Leadership, 13(10).[AQ: 33]

NAS Recruitment Communications. (2007). Recruiting and manag ing the generations. http://www.nasrecruitment.com/talenttips/ NASinsights/RecruitingManagingTheGenerationsWhitePaper. pdf[AQ: 34]

Ortiz, F. (1982). Career patterns in education. Women, men and minorities in school administration. Praeger.

Parsons, T. (1960). Structure and process in modern societies. The Free Press.

Ryan, R. M. (1982). Control and information in the intrapersonal sphere: An extension of cognitive evaluation theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 50–461.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development,

10 Journal of Education 00(0)

and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78. [AQ: 35]

Schmittou, D. M. (2011). The motivating factors of secondary school assistant principals in southeast Michigan and their impact on job mobility (Master’s theses and Doctoral disserta tions, 319). https://commons.emich.edu/theses/319

Scott, W. (2008). Institutions and organizations (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Scott, W., & Meyer, J. (1983). The organization of societal sec tors. In Organizational environments: Ritual and rationality. University of Chicago Press.[AQ: 36]

Sergiovanni, T. (1967). Factors which affect satisfaction and dissat isfaction of teachers. Journal of Educational Administration, 5(1), 66–87.

Simon, H. (1957). Administrative behavior (2nd ed.). The Macmillan.

Strang, D., & Soule, A. (1998). Diffusion in organizations and social movements: From hybrid corn to poison pills. Annual Review of Sociology, 24, 265–290.

Thompson, J. (2008). Organizations in action (6th ed.). Transaction Publishers.

Thompson, J., & Hawkes, R. (1962). Disaster, community organization, and administrative process In G. Baker & D. Chapman (Eds.), Man and society in disaster (pp. 268–300). Basic Books.

Winter, P., & Partenheimer, P. (2002). Applicant attraction to assistant principal jobs: An experimental assessment. University Council for Educational Administration.